The Need for Tailored National Approaches

- Understanding the determinants of self-employment and how they differ across the region is critical if entrepreneurship is to achieve economic goals

- Arab states should be reassessing their strategies, policies, and programs to maximize expenditures on fostering entrepreneurial activity

In many Arab countries, economic integration, the need for economic diversification, occupational preferences for public sector employment, and high youth unemployment rates have prompted the adoption of economic reforms to improve the enabling environment for entrepreneurship. However, understanding the determinants of self-employment and how they might differ across the region is critical if entrepreneurship is to be a solution for the region’s youth unemployment challenge and can ultimately lead to desired economic outcomes.

Differing determinants of entrepreneurship across the Arab region have significant implications for national policies and support programs that might be offered to regional entrepreneurs.

The distinction between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship is becoming increasingly relevant as countries in the region are largely pursuing undifferentiated entrepreneurship policies that are primarily aimed at opportunity entrepreneurs.

We formulated +100 programs to achieve a government's development vision.

Learn about our Public Sector Strategy and Execution services here.

Necessity and Opportunity Entrepreneurship in the Arab World

Since 2001, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), which is an annual assessment of entrepreneurial activity in 100 countries, has distinguished between two types of entrepreneurs: opportunity entrepreneurs who pursue business opportunities voluntarily for personal interest, greater independence, or higher income often at the same time they hold a regular job and necessity entrepreneurs who are engaged in self-employment because they are unable to find better work and self-employment is the best alternative, but not necessarily preferred, employment option (Reynolds, Camp, Bygrave, Autio, & Hay, 2001; Xavier, Kelley, Kew, Herrington, & Vorderwülbecke, 2012)[1].

Analysis of GEM data indicates that innovation-driven countries with higher GDP per capita have higher rates of opportunity entrepreneurship while lower income countries have higher concentrations of necessity entrepreneurs.

GEM data also suggests that a higher percentage of opportunity entrepreneurship occurs in high skill, knowledge-based business services with a greater concentration of necessity entrepreneurs in low and semi-skilled consumer-oriented economic sectors. Growth aspirations also vary substantially based on entrepreneurship types with the majority of necessity-driven entrepreneurs expecting their firms to remain under 5 employees (Reynolds et al., 2001; Xavier et al.k, 2012).

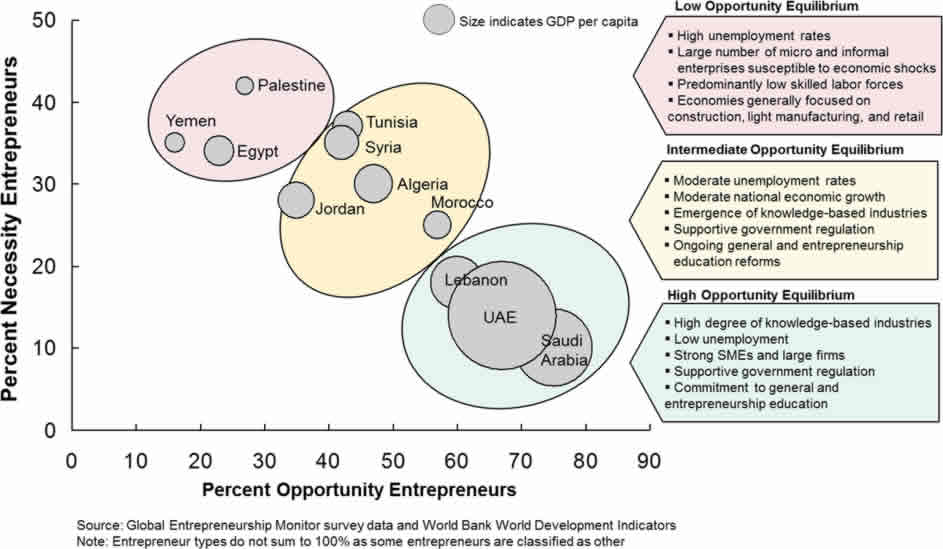

GEM data on 11 countries in the Arab region enables the classification of countries according to their ability to provide a sufficient enabling environment for opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. Arab countries can be classified into three maturity stages which relate economic development, labor market conditions, and industrial structure to the potential for opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. A brief description of each equilibrium phase is discussed below and applied to 11 Arab countries for which GEM data is available in Figure 1.

Low Opportunity Entrepreneurship Equilibrium: A low opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium occurs when an economy adopts a lower value added production orientation when faced with a low supply of workforce skills. In economies facing low opportunity entrepreneurship equilibria, the industrial structure is typically made up of a large number of micro and informal enterprises which are highly susceptible to economic shocks. Small firms are more susceptible to economic fluctuations that can cause changes in unemployment rates or fail to provide sufficient employment opportunities which lead to comparatively high levels of necessity entrepreneurship. Egypt, Palestine, and Yemen, which have high concentrations of necessity entrepreneurs, exhibit low levels of ecosystem maturity in terms of presenting opportunities for opportunity-based entrepreneurship.

Intermediate Opportunity Entrepreneurship Equilibrium: With an average annual GDP growth rate of nearly 3% in 2012 according to World Bank statistics, over two times the GDP growth rate in the OECD, the Arab countries which fall in the intermediate opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium stage are experiencing comparatively moderate levels of economic growth which has been shown by GEM data to lead to significant levels of necessity entrepreneurship (World Bank, 2013). However, the structure of such economies, which cannot be classified as specializing in knowledge-based industries or goods and commodity industries which require low levels of workforce skills, have led to comparatively lower levels of unemployment than in countries in a low opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium. For this reason, such economies also offer significant opportunities for opportunity-based entrepreneurship. Countries at the intermediate opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium stage have implemented economic policies to enhance entrepreneurship and enacted reforms towards improving the quality of education and integrating entrepreneurship within education and technical and vocational education and training systems. Countries at the intermediate opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium stage include Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, Syria, and Tunisia.

High Opportunity Entrepreneurship Equilibrium: Countries in a high opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium are generally comparatively wealthy countries on a GDP per capita basis with a substantial number of knowledge-based industries which provide high skill, high wage employment to a majority of the population. These countries may also have large rates of concessionary public sector employment which provided funding and availability for opportunity-based entrepreneurship. The industrial structure of such countries is characterized by a strong small and medium sized enterprise sector as well as large, sophisticated firms which may be state owned. Countries in a high opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium have implemented economic policies specifically to support entrepreneurship and have achieved significant success in improving the quality of education and integrating entrepreneurship training into education and technical and vocation education and training. The level of economic development, labor market conditions, and industrial structure of such economies is conducive to high levels of opportunity-based entrepreneurship particularly in higher value added service industries. Countries at the high opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium stage include Lebanon, UAE, and Saudi Arabia[2].

Based on the maturity model for opportunity-driven entrepreneurship proposed, the Arab countries exhibit a large degree of diversity in their ability to provide an ecosystem conducive to opportunity-based entrepreneurship.

However, the diversity of entrepreneurial opportunities available in countries across the region has not led to targeted economic policy interventions regarding entrepreneurship at the national level. In several Arab countries, economic policy does not differ significantly based on the higher concentration of either necessity or opportunity entrepreneurs. Most Arab countries are pursuing identical entrepreneurship policies, which include career guidance, funding, business skills training, reducing bureaucracy, and establishing business incubators, without regard to the types of entrepreneurs in their countries and vastly different support needs required by necessity versus opportunity-based entrepreneurship.

Figure 1. Opportunity-based entrepreneurship ecosystem maturity

The Need to Distinguish Between Types of Entrepreneurs in the Arab World

An emerging body of international empirical literature suggests that necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs differ significantly in socio-economic characteristics; motivation and the types of opportunities pursued; and the potential for their entrepreneurial endeavors to create jobs and motivate private investment. Figure 2 summarizes the key differentiating characteristics between necessity and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs according to international empirical studies.

| Category of Comparison | Opportunity Entrepreneurs | Necessity Entrepreneurs |

|---|---|---|

| Age | On average approximately 5 years younger according to empirical studies based on international data | Up to 5 years older than opportunity entrepreneurs in empirical studies based on international data |

| Education | Tend to be more highly educated with education and general labor market experience having a positive impact on earnings and reducing exit rates | Tend to be less educated and benefit more from specific vocationally oriented education found to be related positively to earnings |

| Industry Experience | More likely to have working experience from regular employment in the same industry they are entering | Less likely to have experience from regular employment in their focus industry |

| Motivation | Voluntarily attracted into self-employment by the identification of opportunities; They often leave wage employment or pursue opportunities alongside full time employment | Often driven into self-employment after involuntary job loss or scarcity of employment opportunities |

| Cyclicality | More likely to create ventures when economic conditions are good and unemployment is low; They also choose to create businesses regardless of their employment status | Negative economic shocks that are more likely to affect small firms or increase unemployment push individuals to create businesses |

| Quality of Opportunities Pursued | Create larger businesses in knowledge-based industries which require significant amounts of invested capital and employees generate higher earnings | Less likely to have business ideas with significant growth prospects and more likely to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities in low-income, low knowledge-content sectors |

| Potential for Job Creation | Higher probability of creating additional jobs | Primarily focused on employing themselves and have lower probability of creating additional jobs |

| Firm Survival | Higher survival and lower failure and closure rates | Face a higher risk of failure, or, if they survive, they may produce only marginal businesses, invest insignificant amounts of capital, fail to create further jobs, and earn minimal incomes |

| Capital Investment and Risk Tolerance | Invest higher amounts of capital into their venture and are more risk tolerant | Lower amounts of invested capital and lower tolerance for risk |

| Tendency to Seek External Support | More likely to have built their network to include people valuable in the process of venture creation such as potential customers, cofounders or financiers | Less likely to seek support in the form of professional or personal assistance during venture creation |

These empirical findings present strong evidence that national training and support programs for entrepreneurship require significant tailoring to meet the needs of both necessity and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs.

In many Arab countries entrepreneurship policies are not necessarily aligned with macroeconomic and other critical policies for economic development.

By not accounting for particular needs of different types of entrepreneurs, regional entrepreneurship policy is designed around a one size fits all approach which is particularly lacking in regards to serving necessity-driven entrepreneurs. Based on the proposition that entrepreneurship policies in a given country should reflect the mix of necessity versus opportunity-driven entrepreneurs operating in the country, Arab countries, based on the equilibrium stage they fall into, should have significantly different, contextually dependent economic policies surrounding entrepreneurship.

Implications for policy and practice

Due to the scarcity of empirical work on necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship in the Arab region, it is difficult to formulate specific prescriptions at the national level. However, this exploratory analysis shows that strong differences exist between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs which have not been accounted for in regional entrepreneurship policies. Entrepreneurship policy across the region fails to differentiate between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs favoring a one size fits all approach that is largely shaped by programs that serve opportunity-driven entrepreneurs. In doing so, tailored offerings based on the characteristics of different types of entrepreneurs are rarely considered.

International empirical findings, assuming applicability to the Arab region, suggest a strong case for more tailored national entrepreneurship policies in the Arab region which reflect the mix of necessity versus opportunity-driven entrepreneurs operating in particular countries.

Entrepreneurship in countries at a high opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium, which likely includes all of the Gulf countries, is presumably much different than entrepreneurship in countries like Egypt, Palestine, and Yemen in a low opportunity entrepreneurship equilibrium. Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs differ in socio-economic characteristics; motivation and the types of opportunities pursued; and the potential for their entrepreneurial endeavors to create jobs and motivate private investment. These differences are potentially unexploited policy levers which might serve as guidance for targeted national policies.

Regional governments must avoid classifying all entrepreneurs as a homogeneous group driven and offering undifferentiated support.

Instead, they can introduce targeted training programs and support, contingent financing, and subsidies which might better serve both necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs. If entrepreneurship is to continue to be championed as a panacea for the region’s youth unemployment challenge and resolving structural economic and labor market issues, then such tailored policy measures appear long overdue. Figure 3 presents a summary of potential components of regional entrepreneurship policy which may need to be reconsidered to more effectively meet the needs of both opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs.

| Components of Entrepreneurship Policy | Typical Opportunity Entrepreneur Approach in the Arab Region | What Might be Needed to More Effectively Reach Necessity Entrepreneurs in the Arab Region |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship Policy Approach | Policies view entrepreneurs as a segment of the national economy who can take advantage of all programs and may not distinguish between small business support and policies which support entrepreneurial ventures | Defined policies and programs to meet the specific needs of necessity entrepreneurs and other country specific challenges |

| Entrepreneurship Education | Early and post-secondary entrepreneurship education and business skills training at university and non-university based business incubators | Support for training in specific technical and vocational areas potentially below the post-secondary level in addition to early and post-secondary entrepreneurship education and business skills training |

| Access to Finance | Increasing the supply of capital through direct loans and venture funds | Public financing programs that may target a broader range of industries along with a stronger focus on helping entrepreneurs access capital by focusing more on business issues such as management skills and evidence of a solid business plan |

| Optimizing the Regulatory Environment | Macroeconomic approach to tax and regulatory policy focused on changes in laws (e.g., general tax reductions) and regulations that affect everyone doing business | Policy impact analysis to determine if regulatory changes are sufficiently focused on the needs of necessity entrepreneurs; Policies that most benefit these businesses are those that defer expenses, allow companies to convert tax incentives into cash, and lower development costs |

| Technology Exchange and Innovation |

Cluster development and leveraging public funds, that encourage university-private sector collaboration |

Benchmarking and evaluating the benefits associated with state investments on necessity entrepreneurs and whether they are adequately served by such initiatives |

From this analysis, it is clear that a large number of Arab states should be reassessing their strategies, policies, and programs to maximize expenditures on fostering entrepreneurial activity. This article is designed to raise issues to spur a more informed debate around the impact of entrepreneurial policies in the region and promote national policies that accommodate, when necessary, both opportunity and necessity entrepreneurship.

[1] Caliendo & Kritikos identify a third classification of push-and-pull entrepreneurs who are driven by a mixture of push (unemployment or difficulty locating a suitable job) and pull factors (personal interest, greater independence, or higher income). Though they express mixed motivations for pursuing entrepreneurship, push-and-pull entrepreneurs are more similar to opportunity entrepreneurs.

[2]Upper-middle income countries like Lebanon may not be able to emulate many of the policies and practices of the richer Gulf Cooperation Council countries which generally offer highly paid public sector work and social benefits that affords many individuals the time and resources to pursue opportunity-based entrepreneurial endeavors alongside full time work. This suggests that even at particular equilibrium stages, countries will likely need to follow country context dependent policies aligned with national resources available to support entrepreneurship relative to other socio-economic government aims.