Is a "sin tax" the best way to tackle the health risks associated with high caffeine consumption?

- The UAE's national technical regulations suggest an evolving trend toward more restrictive formulation, distribution, and labeling requirements

- The availability of alternative sources of caffeine such as soda, coffee, and even snacks are likely to hamper the intended objectives of a 100% tax on energy drinks

Since being introduced to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in 2000, demand for energy drinks has surged, particularly amongst youth. There are no firm figures on the total value of the GCC energy drinks market. However, the Council of Saudi Chambers estimates that Saudis spend over $1.5 billion a year on energy drinks.

The energy drink market in the UAE has been valued at approximately $200 million.

If demand in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar is roughly on par with other GCC countries, the total GCC market for energy drinks could be worth as much as $2 billion per year.

Efforts to Regulate Energy Drinks in the GCC

Given surging demand and high rates of youth consumption, some estimates show that 19 to 29 year olds make up 70% of energy drink consumption, GCC countries have collectively, through the GCC Standardization Organization, and individually, though national laws, pursued public policies to regulate energy beverages on public health grounds.

While it is common public perception that government impetus to regulate energy drinks stems from high levels of sugar content relative to other beverages, GCC regulator concerns relate more to caffeine levels and the marketing of energy drinks as supplements that enhance athletic performance and increase energy.

Regulators and health advocates believe youth and athletes who consume energy drinks are not fully aware of the health risks of excessive caffeine intake.

Within the GCC Standardization Organization (GSO), the Emirates Authority for Standardization and Metrology (ESMA) and the Saudi Standards, Metrology, and Quality Organization (SASO) have exhibited significant influence on energy drink technical standards which have formed the basis for national regulations on energy drinks in other GCC countries.

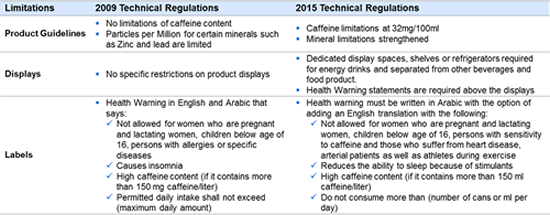

In 2009, the GSO issued non-binding standards for energy drinks which were subsequently revised in 2015. The exhibit shown below shows how the UAE translated the 2009 and 2015 non-binding GSO standards into national level technical regulations to establish product, display, and labeling requirements for energy drinks in the UAE. The UAE’s national technical regulations for energy drinks show an evolving trend of more restrictive formulation, distribution, and labelling requirements.

A number of the recommended standards issued in the 2015 GSO Technical Regulations which were not adopted by the UAE in its national level technical regulations on energy drinks potentially foreshadow more stringent GCC regulation of energy drinks in the future. Some of the proposed standards from the GSO standards for energy drinks which did not make it into national technical regulations in the UAE but which could be adopted by other GCC countries include:

- Limiting the maximum capacity of each container to 250 ml

- Prohibiting sale of energy drinks in government restaurants or canteens, educational and health institutions, and public or private sports clubs

- Prohibiting print, audio, or visual advertising promotions

- Prohibiting sponsorships of sports, social, or cultural activities and marketing/promoting energy drinks through such activities

- Prohibiting free product distribution

However, given the pioneering influence of ESMA and SASO on other GCC countries, it is likely energy drink regulation in Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar will likely closely follow energy drink regulations currently being considered in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Several more restrictive regulations (shown in the exhibit below) currently being considered by the governments of the UAE and Saudi Arabia which would further limit energy drink sales and consumption potentially serve as bellwether of regulations that may be in the pipeline in other GCC and Arab countries.

The Emergence of an Energy Drinks Sin Tax in the GCC

As in other countries in the world, extending “sin taxes’” to certain foods and products is increasingly seen in the GCC as a practical response to improving public health while increasing government revenues. In 2015, the governments of Saudi Arabia and Bahrain submitted a request to the Committee on Financial and Economic Cooperation of the GCC to consider a 100% excise tax on energy drinks. In January 2016, it was announced in the media that an agreement on the proposed energy drink tax is expected to be signed by all GCC member states by the middle of 2016 with final approval and implementation expected by early 2017.

The proposed 100% tax on energy drinks would be one of the first sin taxes introduced in the GCC.

However, there is mixed evidence on the effectiveness of sin taxes as a policy instrument to promote improved public health. Empirical studies of the most common excise taxes in other countries, such as taxes on cigarettes and gasoline, usually conclude that they are fully shifted to consumers. It is generally accepted that higher prices lead to lower levels of consumption. Yet, consumers can easily switch to consuming other high caffeine content products if the prices of energy drinks rise across the GCC.

Unfortunately, real world evidence has found sin taxes, such as the one being proposed for energy drinks in the GCC, have only modest effects on consumption and little or no effect on public health.

While it remains unclear how the 100% excise tax on energy drinks will ultimately affect consumer prices, a recent study in the US which assessed the efficacy of increases in sales tax rates as high as 12% on soda suggest that even large taxes do not affect consumption or public health outcomes.

An energy drink consumer faced with higher prices might switch to a number of alternative products, such as soda, coffee, tea, or even snack foods, which have equal, and in some cases higher levels, of caffeine than energy drinks. If the intent of the proposed GCC tax on energy drinks is to limit overconsumption of caffeine, it is unlikely to be effective if it is not extended to other foods and drinks with similar levels of caffeine - his is due to substitution effects.

Consumers faced with higher energy drinks prices will simply consume caffeine from other sources.

For this reason, the energy drink tax may become only a stealth tax that is ineffective in reducing energy drink consumption and limiting caffeine intake. It is certainly possible that the energy drink tax could be raised to the point at which it does work, but this may place undue burden on consumers and ultimately the cost of the tax may exceed any savings realized by the healthcare system.

What is the Alternative?

GCC public health regulators have very few policies which they can pursue in regulating energy drinks and influencing consumer behavior – reducing availability, restricting marketing and promotion, and increasing prices through taxes. GSO standards and national level laws have already targeted availability and promotion. However, evidence from around the world suggests that sin taxes deliver little benefits.

A more effective approach may be to devote sufficient resources to existing fledgling national campaigns that increase awareness amongst GCC youth of the harmful heath consequences of caffeine over consumption rather than introducing a tax that is likely to be ineffective. Awareness efforts can solicit funds from a range of food and beverage companies, not solely target energy drinks companies, since excess consumption can occur by consuming caffeine from any food or beverage source.

If the energy drinks tax is taken forth, the proposed tax on soda should be increased to be at least as high, and the inclusion of other high sugar and caffeinated food and beverage products should also be considered for taxation.

To date, no country has effectively used food and drink taxes to influence public health outcomes. As Tahseen Consulting mentioned in our recent article on tackling the regional diabetes epidemic, perhaps a more urgent public health challenge for GCC regulators is to address the sizable budget gap for preventing and treating diabetes. Given the magnitude of the diabetes epidemic in the Arab World, there is pressing need to increase regional spending on national prevention strategies.