How the Arab world is shifting the global balance of power away from Big Tech

- MENA governments are becoming increasingly worried about the shifting balance of power between governments and global technology companies

- In a bid to take back control, many governments are developing their own alternatives to global apps with varying degrees of success

A recent episode of the American comedy show “Silicon Valley” provides a glimpse into the changing internet and technology landscape in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). In the show – a parody of entrepreneurs vying for success in the Bay Area tech hub – coder Jian Yang is seen replicating American platforms for Chinese audiences including ‘New Facebook’ and ‘New Snapchat.’ The character’s lack of ingenuity is underscored by the names of the replicas, which are uninspiringly called by their original brand name preceded by the word ‘New,’ presumably in an attempt to skirt trademark infringement and similarity disputes.

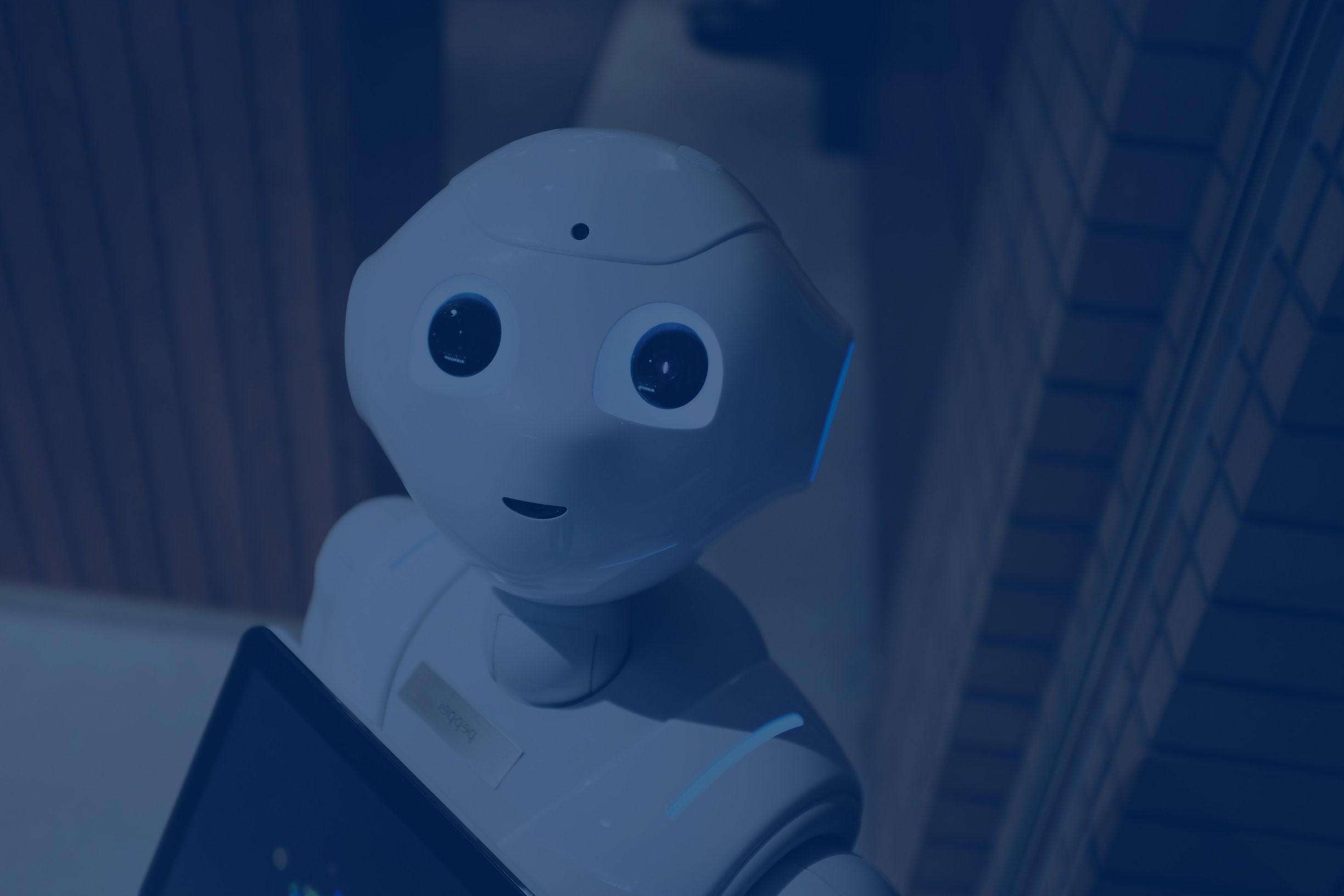

This scene from “Silicon Valley” is, in fact, a parody grounded somewhat in the reality that is playing out in the global tech industry in several regions globally. For example, in the MENA, governments – as opposed to private entrepreneurs – are taking the lead in creating a ‘New Internet’ as the region’s digital economy is booming and governments become increasingly uncomfortable with ceding control to foreign tech companies.

The MENA’s New Internet 1.0

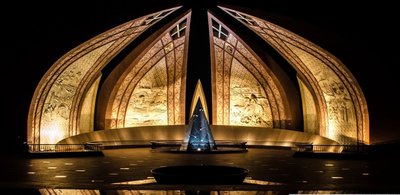

In Egypt, the short-lived Egypt Face was the ‘New Facebook.’ In Iran, Soroush is the ‘New Telegram’ and ‘New WhatsApp.’ And in the UAE, Botim and C’Me are the ‘New Skype,’ and Dubai’s Department of Tourism and Commerce Marketing’s Tourism 2.0 sounds a lot like the ‘New Booking.com.’ There have also been several regional attempts at a ‘New Uber’ by state-linked transport regulators and operators. These are just a few examples of a growing trend in which MENA governments are becoming increasingly worried about the shifting balance of power between governments and global technology companies.

MENA governments are concerned about the private sector’s control of personal data, wary of imbalances between international and domestic laws when it comes to accessing data and online speech, and worried about losing control over national narratives.

These concerns have pushed MENA governments to take matters into their own hands by developing and launching their own apps to compete with international tech companies. Government involvement in these apps can be overt, such as many of the websites and apps in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which are positioned as extensions of smart government and city initiatives, or less obvious, such as in the case of Egypt Face, where details about government involvement were less forthcoming.

The uptick of new internet platforms launched with state backing is a relatively recent phenomenon as the digital economy has surged in the MENA.

More often than not, these websites and apps are heavily influenced by already successful global tech apps, websites, or services. In some cases, governments have not only supported domestically-produced copycats, but have also limited or blocked access to competitor apps or imposed unworkable registration and licensing requirements on global tech companies, to promote adoption of domestically-controlled and supported apps and websites.

Over-the-Top Apps are a Key Battleground

In the telecommunications sector, in particular, MENA governments and government-owned telecoms are creating services to directly compete with established global tech companies with varying degrees of success. For example, several MENA countries are making it challenging to access VoIP services such as Skype, FaceTime, and Viber due to the inability of international tech companies to comply with regional user data access regulations and lawful intercept requests. Given their commitments under international law, global tech companies view data requests by regional authorities as an overreach by domestic governments, while domestic policymakers and law enforcement view international tech companies’ reluctance to provide data as a violation of sovereignty and domestic due process.

In some cases, data access and intercept requests are made conditional to attaining domestic licenses for services, creating a stalemate in which governments, telecoms, and international tech companies remain at loggerheads with no resolution in sight. With VoIP, for example, government-owned telecoms have launched their own competing apps and are exploring alternative technologies like VoLTE.

Many of these current squabbles between government, telecoms, and international tech companies are reminiscent of the 2010 GCC threat to ban users of BlackBerry mobile phones from using email, instant-messaging, and web-browsing services due to its encryption technology.

Across the Gulf, in Iran, use of the messaging app, Telegram, is ubiquitous after the platform became indispensable as an organizing tool during the 2017 anti-government riots. This prompted the judiciary to ban the platform and the government to incentivize the creation of a local messaging rival called Soroush. While state reports boast that millions of Iranians have signed up for Soroush, activists point out that further user growth is limited by the app’s government affiliation. Iran has also developed local versions of Facebook (Cloob - a Facebook clone that ceased operations), Instagram (Lenzor), YouTube (Aparat), and Netflix (Filimo).

In March, Egypt’s Communications Ministry announced the creation of a Facebook-like social network called Egypt Face and hinted that several other social platforms were in the works. These copycats were all purportedly developed to help protect Egyptian citizens’ data and bolster national security.

‘Egypt Face’ is no longer online, and it is unlikely that it would have unseated Facebook, which has over 30 million registered users in the country.

There is also a recent focus on travel and tourism by countries like the UAE and Morocco. Morocco, for example, recently announced that Airbnb and Booking.com would be subject to a new tax in 2019, which would allow domestic online travel platforms to compete with international players. There are emerging signs that travel and tourism could be the next focus of MENA governments.

Mixed Success Will Inspire the MENA’s New Internet 2.0

The success of regional governments in the New Internet 1.0 varies largely due to how new government apps compare to their global counterparts, how committed users are to existing platforms, and local political, social, and competitive factors. New VoIP services, such as the UAE’s Botim and C’Me, have had moderate levels of success, with users complaining about poor call quality and dropped calls. In Iran, despite the continued usage of Telegram through VPNs, the replica app Soroush has roughly 12 million active users. In Egypt, despite much government fanfare around its launch, Egypt Face was effectively dead on arrival with users mocking the site by creating fake accounts in President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s name and testing the limits of expression by publishing posts about the country’s human rights record.

Responses from companies whose services have been replicated or blocked have been largely muted.

For example, companies such as Microsoft and Apple have stated that they are working with authorities to get VoIP services, such as Skype and FaceTime, licensed in the UAE. One potential way of resolving government standoffs over market access is quiet compliance. There is a movement by Silicon Valley giants to modify their service offering in a bid to comply with local regulations in order to gain access to large overseas markets. For example, Google recently made headlines when it announced that it was working on a version of its services to be offered in China, which will comply with local censorship and data localization regulations, to reenter the Chinese market. However, this is not a practical solution for most international tech companies in the MENA due to the market’s comparatively small size.

The recent surge in tech employee activism to avoid bending to local market pressures also brings into question the practicality of such quiet compliance strategies in the MENA.

Generally, regional users have been reluctant to use government-led copycat websites and apps due to information privacy and online freedom concerns. However, as popular internet services gain market share and control and monetize vast amounts of user data, the same concerns potential users have voiced in the MENA about using government apps and websites are sounding strikingly similar to the global criticism being levied at international tech companies about data privacy and freedom of expression. With state-sponsored apps and services, copycats as they may be, there is a degree of democratization of the Internet, where users are not limited to choosing from any particular service, but rather have multiple options to choose from, including home-grown ones.

The long-term success of the MENA’s ‘New Internet’ is far from certain, and “Silicon Valley’s” parody could become the region’s reality.

While there are examples of clear failures, like Egypt Face, the MENA’s New Internet 2.0 is likely to benefit from these lessons in its ongoing struggle to embrace the digital economy while at the same time not ceding power to global, and increasingly regional, technology companies.